Vo Nguyen Giap, the brilliant Vietnamese

general who died last week at the age of 102, became a legend in his lifetime as

one of the greatest military leaders of the 20th century. Equally important, he

became a source of inspiration to millions of young people the world over who

spiritedly opposed and protested against the United States’ invasion of and war

on his country.

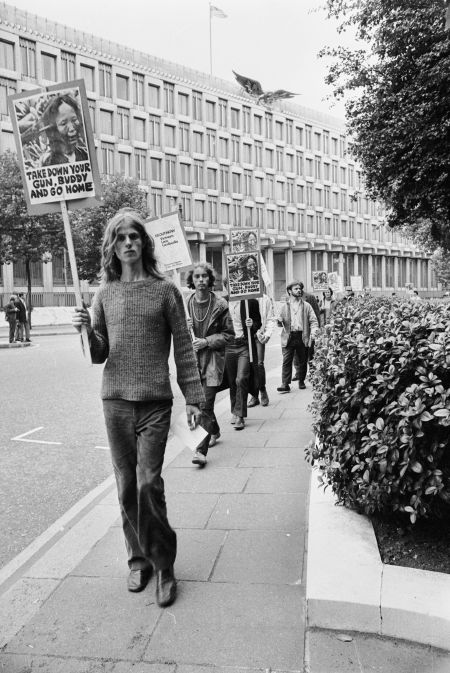

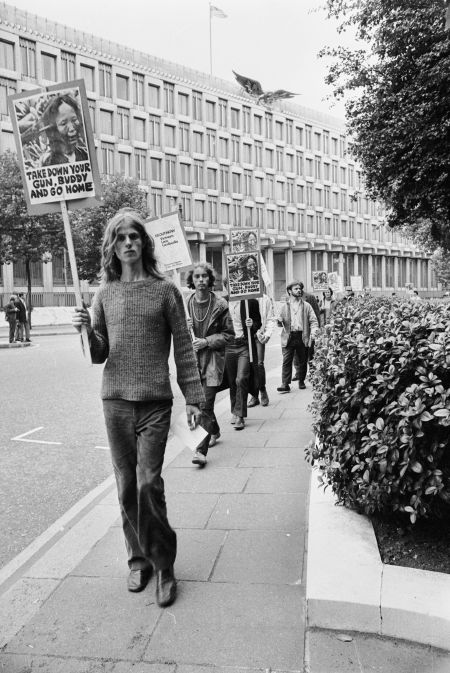

The antiwar movement ignited some of the most radical and creative

mobilisations the world has ever witnessed, including the landmark May 1968

revolt in France, and politicised a whole generation.

Giap became a hero in India too, where progressive political, student and

trade union movements coined slogans expressing solidarity with the

revolutionary Viet Cong forces fighting the Americans, such as “

Aamaar Naam,

Tomaar Naam, Vietnam, Vietnam (My name, your name, Vietnam, Vietnam)” and

“

Ganga, Mekong Ek Naam, Vietnam, Vietnam.”

A teacher and journalist with no formal

military training, Giap enlisted himself in a ragtag Communist insurgency in the

1940s and forged it into a highly-disciplined force that brought about the end

of France’s Indo-Chinese empire and reunited a nation divided by the Cold

War.

Giap first masterminded the defeat of the French forces occupying Vietnam,

and then led North Vietnam’s forces against the South’s puppet regime until the

US had to beat an ignominious retreat from the country in 1975, when a

helicopter flew out the remnants of US troops from the roof of the American

embassy in Saigon.

This ended one of the most brutal wars in history, in which three million

civilians were killed (of a total population of 32 million), vegetation in huge

swathes of land was destroyed by defoliants such as Agent Orange, cities were

indiscriminately bombed, and numerous atrocities were sadistically committed

against unarmed peasants, such as the infamous My Lai massacre.

As Giap put it in an interview in 2005 on the 40th anniversary of the fall of

Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam under US occupation: “No other wars for

national liberation were as fierce or caused as many losses as this war.”

The war was one of the bloodiest

chapters, if not the bloodiest one, in the history of the Cold War, fuelled by

the US’s global offensive against Communism and national liberation movements

seeking a modicum of independence and sovereignty. The US launched a ruthless

campaign in Vietnam to bomb it “back to the Stone Age” and created concentration

camps known as “strategic hamlets” to punish and demoralise non-combatant

civilians, besides funding clients and blacklegs.

All this was to ensure that the Viet Cong, politically led by Ho Chi Minh,

would be militarily defeated and their country economically and socially ruined.

The opposite happened. Giap’s brilliant military strategy of a people’s war

played no mean role in bringing about this outcome.

The US’s historic debacle in Vietnam served to kindle the hope the world over

that ordinary people determined to fight invasion, tyranny and injustice could

win against the world’s mightiest nation no matter how poorly equipped and armed

they might be. Like Fidel Castro’s successful and heroic defiance of the US, the

victory of the Vietnamese revolution became a symbol and source of hope for

movements in scores of countries against imperialism and for emancipation of

their people from exploitation and oppression.

Giap devised a combination of military strategies that would combat US and

South Vietnamese troops both by conventional means and through guerrilla

warfare. Crucial to this was winning peasants over to the cause of national

liberation. Giap had closely studied the military teachings of Mao Zedong, and

believed that political education and grassroots popular support for sustained

guerrilla warfare were necessary for the revolution to succeed.

Giap’s military methods were perfected

in the war against the French occupation after World War Two. In 1954, Giap

famously defeated the French army’s elite troops and its foreign legion at Dien

Bien Phu, near the border with Laos, where they had established a stronghold. In

May 1954, Vietnamese forces under the command of the Viet Minh, the military

wing of the Vietnam Independence League, besieged Dien Bien Phu.

The Viet Minh troops wore sandals made of used car tyres and had so little

mechanical transport that they had to lug their artillery piece by piece over

the mountains around the encampment. Yet, after an eight-week siege, they

inflicted a crushing defeat on the French troops after using artillery to block

supplies to them. That battle has become a part of military strategy books

worldwide, and even earned Giap the grudging admiration of French generals.

But military strategy was only one source of Giap’s success. The timing of

the attack was a political masterstroke, coinciding with the day that

negotiators met in Geneva to discuss a settlement to the conflict. Faced with

the debacle, the French conceded defeat and agreed to withdraw. The country

split into a Communist-ruled north and a non-Communist south, which Giap

eventually managed to reunite by defeating the US-backed and far better armed

south Vietnamese forces in 1975.

Dien Bien Phu forced out France of Indochina altogether and greatly

strengthened anti-imperialist movements in Asia.

Against his more powerful American adversaries, Giap used a strategy based

more on guerrilla warfare than conventional attacks, but only after his massive

operation called the Tet offensive of 1968 collapsed, with heavy Viet Minh and

Viet Cong casualties.

Militarily, the Tet offensive was a

failure. But politically, it succeeded in showing that the Americans were

vulnerable. It greatly reinforced the growing domestic opposition in the US to

the war, whose savagery became increasingly apparent thanks to television

coverage and the sight of body bags returning home. As Giap said later, the

offensive “affected the people of the United States more. Until Tet, they

thought they could win the war, but now they knew that they could not.”

Giap firmly believed that the key to military success against the US would

lie in politics -- the people’s conviction that they are fighting for a just

cause; they will therefore forge the will to win despite the greatest possible

adversity. The people become the sea for the guerrillas who are like fish, in

Mao’s famous analogy.

General Giap, known as the Red Napoleon, has often been compared with

legendary military geniuses like Wellington, MacArthur and Rommel. Perhaps a

more apt comparison would be with Soviet general Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who

fought the white counter-revolutionary forces during the Civil War and commanded

the Red Army with dazzling success -- until he was victimised in Stalin’s Great

Purges and executed.

In personal life, Giap was no aggressive

militarist, unlike many people in the so-called “strategic community” in India

and abroad. He was a gentle and charming person, erudite and well versed with

Western literature and music, as well as classical political economy. He enjoyed

Beethoven and Liszt.

Although a general, and then a defence minister, Giap remained sensitive to

social agendas in contemporary Vietnam. “In the past, our greatest challenge was

the invasion of our nation by foreigners,” he told an interviewer. “Now that

Vietnam is independent and united, we can address our biggest challenge. That

challenge is poverty and economic backwardness.”

There may be a lesson in this for us Indians too.

The Vietnamese fought well enough to cause the defeat of the French...on the battlefield, the US was not defeated on the battlefield in Vietnam...it was defeated on the floor of the politics...

ReplyDelete